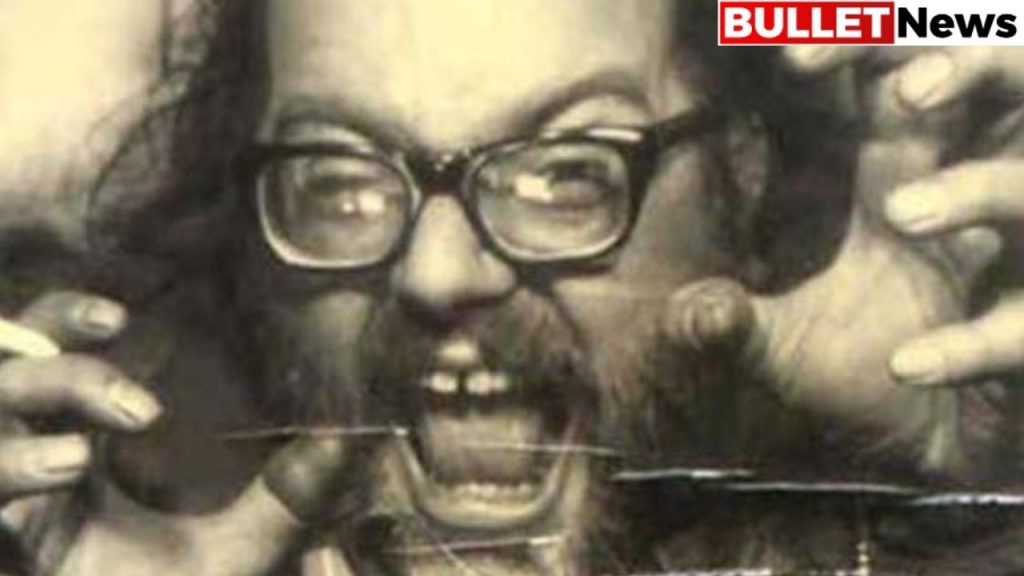

Part documentary and part biographical, Del Close’s story is told by director Heather Ross. And focuses on the late 1980s, as Close attempts to recreate her life story. Through DC Comics’ 18-issue anthology of horror comics, Wasteland.

James Urbaniac plays Close in these scenes.

Teaming up with his co-writers (played by Loki’s Josh Fadem, Better Call Saul) and Cutter (played by Close’s actual student from Veep, Matt Walsh). Another scene reveals Lennon Parkham and Lauren Lapcus. As DC Comics connections in the office dealing with Close on the phone. In a separate hallucination, Near Urbaniac interacts with Patton Oswalt. To manifest his comic book villain and later with Paul Scheer as a talking mouse.

Meanwhile, the high-talk that Close uses in his comics revolve around comparisons and contrasts with his real-world story. From humble beginnings in Kansas to the fortunately short professional ass, “torch man” side. Who faces a random invitation to join the new improv troupe, The Compass Players. And creates improv as an art form unto itself and composed the first “kitchen rules” for professional improv on stage. Close worked there with other future comedy legends such as Mike Nichols and Elaine May.

While Nichols and May broke up and starred as a duo in New York. Close first found himself in San Francisco, wherewith a Committee group. Whose members were future TV sitcom star Howard Hesseman of WKRP Cincinnati and class leader. Who found his three-act improv structure called The Harold? He also played with Ken Keese’s hilarious jokes. Close then directed The Second City in Chicago and Toronto during the 1970s and 1980s. Teaching future stars like John Belushi and Bill Murray in Chicago and Eugene Levy. And fellow SCTV actor Mike Myers in Toronto.

Closing arguments with The Second City over the viability of improv.

As an art form that audiences would gladly pay to see on stage. As well as Closing personal disabilities and substance abuse, fired him from The Second City. But he found a new partner with Charna Halpern in the 1980s. Who was ready to head to the ImprovOlympic in Chicago, where Adam McKay, Tina Faye, Amy Poller, Chris Farley, Tim Meadows and many other stars still working on improv to go all-in. In today, their beginning. He even served as credit advisor for SNL before sending many of his students from Chicago to 30 Rock.

Odenkirk tells the origin story of Second City when he visits Chicago as an ambitious comedian in 1981 but under the guise of covering his college radio station and interviewing Close, who has just been fired and recently resigned. Odenkirk keeps the tapes, which begin with Close begging for young Bob’s drugs and claiming a broken window in his apartment resulted from a “jealous husband”. Odenkirk laughed nervously and again and again.

“I don’t know these things. I’m a kid from Napierville. But if he says he turned down Coca-Cola and did it by going to witch ceremonies, then I believe him,” Odenkirk said now, looking back. “It was crazy that I left the Dell house so excited to do comedy and be in show business.

Another memorable moment comes at the end of the film:

From the old clip of unknown origin to the younger Tina Faye, who makes a mocking confession while sitting and crying right in front of the camera: “It’s a cult. Yes, ImprovOlympic is a Cult. And I’m into it. One night these eight people came to me out of nowhere and were like surly white boys in khakis and told me that I had to go with them and that I couldn’t deny anything they said and that I had done it. To increase their devotion and, you know, the next thing I know, I’m going to write a check to Yes, And Productions!

As much as I love using Urbaniac for Close or other comedians who reenact real or imaginary scenes from his life, I’m not sure if he adds much to my narrative or understanding of Close.

As our spokeswoman, Michaela Watkins can take a moment to see how Closes’ cult of personality may have blinded her to the idea of winning anyone but white people to her cult of improvisation. But the film’s overall task seems to be less questioning of reality but rather to perpetuate and celebrate Close’s status as a mythologist.